The Henry

Loaded on Sunday and fired all week

See now also for Colt: http://outlawscolts.jouwweb.nl/

Guns of Many VoicesWild West Magazine, October 1990

|

|

The 16-shot Henry Repeating rifle served frontiersmen well on "the drop edge of yonder"

|

|

After the Civil War the weapon called by Rebels "that damned Yankee rifle that can be loaded on Sunday and fired all week," the Henry repeating rifle, endured through the late 1860s as the "boss gun!' for men who lived on the frontier. There were few plains, basins or ranges between the Rio Bravo del Norte and the Columbia that did not see the sun catch the mellow glow of its brass frame or echo to the crack of its .44-caliber cartridges.

For as long as men had used firearms, they had felt the need of a light, handy weapon that would fire many times from one loading. Most attempts to fabricate such arms resulted in weapons that were unsafe or too complicated to be reliable or manufactured in any large numbers. The 1850s saw some progress made in the introduction of the celebrated Volcanic rifle in 1854.

The lever-action Volcanic rifles and pistols were intelligently conceived, but hampered by their erratic ammunition. The cartridge consisted of a conical lead projectile with a cavity in its base. The indentation held a light charge of powder and was seated with a perforated cork disc. A fulminate of mercury primer set in the disk's center provided ignition for the powder charge when struck by the gun's firing pin. While the Volcanic had perfected the basic action of the later Henry and Winchester rifles, it was too erratic a performer to win many adherents

The basic idea was not lost, however, and When B. Tyler Henry joined the reorganized New Haven Arms Company of Connecticut in 1857, he designed a cheap, reliable rimfire cartridge that made perfect fodder for the newly improved Henry rifle. It was a rimfire that detonated when the firing pin struck anywhere on the rim. Patented in October 1860, the repeater boasted 16 rounds ready in the magazine to be chambered, and the previous cartridge ejected with just a flick of the wrist.

The Henry won immediate fame in the Civil War, but surprisingly few sales resulted to the national government. Although several Union regiments were armed with the Henry, the authorities in Washington purchased only 1,731 of the repeaters, giving the lion's share of government patronage to the rival Spencer. Encouraging to the manufacturer, 880 of the 1,731 government arms were later bought by soldiers upon their discharge.

Many of those veterans headed westward in search of new opportunities. The Henry would go with them in 1865, but it was already a familiar sight on the frontier. As early as May 1863, one California dealer ordered 10 cases of Henrys, and wrote that even at $75 apiece, the repeaters were selling well. Territorial Governor William F. Arny of New Mexico received an engraved Henry as a gift from Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in August of that year, and by September 1864, at least one shipment of 500 rifles had reached Chicago for sale on the Western markets. The Chouteau Trading Company at Fort Benton, Montana Territory, was also selling Henrys that year. It quickly became a popular arm among the plainsmen. Serial No. 504 still survives, bearing the inscription "F.W. Binger Salt Creek, Neb. 1864."

By the spring of 1865 the war was over and thousands of surplus Spencers flooded the market at low prices the Henry could never hope to match. Still, many men who were headed west to what was commonly called "the drop edge of yonder" preferred the 16-shooter to the cheaper Spencer with its 7-round magazine. One of the earliest postwar emigrants to carry the Henry was George Ray, who joined a small train of 25 wagons with his family as it braved the heart of the Sioux country in the Dakotas. One August day in 1865, Ray mounted a horse and left the train to hunt antelope, leaving his wife to drive the wagon. He was two miles away from the caravan when it came under attack and a band of warriors sought to cut him off from his companions. Captain James B, Loomis and a detachment of the 7th Michigan Cavalry arrived on the scene a few hours later and broke the siege, but by then Ray had staged a one-man demonstration of what the repeater could do against heavy odds.

"He had a Henry rifle ... a 16-shooter," reported Loomis, ...and he determined to make a fight of it. The Redskins rode in a circle as usual out of range, waiting for him but he not wishing to waste a shot, held his fire for them. Seeing that he did not shoot, they began drawing in their line until Ray knew that they were in range and he fired, killing one the first shot:' By that time he had come within sight of the wagons and saw them surrounded by more Sioux. "Then he told me that hope died out in his heart:' wrote the cavalryman, "but he knew his fate if taken so determined to fight until he was killed. For two hours and a half, he fought them single-handed, breaking both lines and gaining camp in safety." His wife had stood by the wagon and given covering fire with a Wesson rifle as he made his break for the train.

That summer of 1865 saw the Henry in use on every quarter of the frontier. Albert J. Fountain, a New Mexico settler, saved his own life and ended the careers of several Navaho warriors with a 16-shooter during that bloody season. Fountain had originally come to that arrid territory as a trooper in the 1st California Infantry when General James E. Carleton marched east from the Pacific to secure New Mexico and Arizona from Confederate invasion in 1862. Two years later Lieutenant Fountain was mustered out and decided to make a home in that savage expanse of desert and sierra. Commissioned a captain in the territorial militia, he soon won a name as a seasoned Indian-fighter.

In June 1865, Chief Ganado Blanco led his Navahos off the reservation and began raiding the Rio Grande settlements below Santa Fe. For two weeks Fountain and his scouts patrolled the river's fords, hoping to ambush the hostiles. Early in July he and a lone companion, Corporal Val Sanchez, probed the mountains that fronted the river to the east of the dreaded Jornada del Muerto a wasteland of rock and scrub that ran for 90 miles above the village of Dona Ana. Both men carried revolvers and the Henry rifles that had been recently issued to the militia. They picked up the Indians' trail and followed it out of the mountains and across the Jornada as they swung northward. When the braves grew wary and back-tracked to find their pursuers, Fountain and Sanchez made a break for a mountain pass that led to Fort McRae, the nearest army post.

Riding hard, they seemed to have shaken off their enemies by the time they reached the narrow defile. Fountain was suspicious and feared that an ambush already awaited them in its thorned gullet. Taking the lead, he cautioned Sanchez to take another route to the fort if he was bushwhacked. The officer entered the gloomy notch in the mesa with his Henry at the ready.

He had almost reached the head of the pass when his horse shied, and he looked up into the bore of a Navaho rifle. The brave fired just as the horse spooked, and the bullet tore into its head, killing the animal instantly. Fountain was pinned beneath its carcass. "The first shot was followed by a volley and as I went down crushed and stunned under my dead horse, an arrow passed through my left shoulder, a bullet entered my left thigh, and an arrow severed the artery in my right forearm:' recalled Fountain. "As I lay crushed and bleeding the Indians rushed on me. The pass was so narrow that but one could approach me at a time. Lying on my back under my dead horse I fired shot after shot from my repeating rifle. I had no occasion to look through the sight as my assailants were not three yards from me."

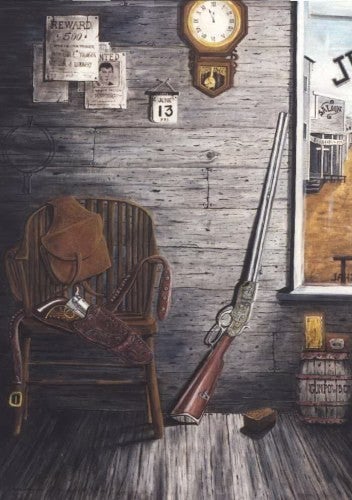

(foto; Henry Rifle .44 RF )

In less than a minute, Fountain said, he had pumped 10 rounds from his smoking Henry and broken the Indians' will to fight. The last brave he saw rushed up to within six feet of him with lance upraised. Fountain extended the Henry in one hand, pistol-fashion, and dropped him in mid-stride. The tribesmen kept watch from a safe distance as Fountain recharged the gun's magazine and used its sectioned cleaning rod to wind a tourniquet around his bleeding arm. Sanchez had bolted for Fort McRae, and when help reached Fountain the next morning, the Navahos had departed. For the next 30 years Fountain would play an increasingly prominent role in New Mexico affairs, becoming one of the leading political figures in the territory before his mysterious murder in 1896. He owed his full life and distinguished career to Tyler Henry's magnificent repeater.

The Henry continued to enjoy mounting popularity in the immediate postwar years. Veteran plains freighter August Santleben of Texas carried one of the first 16-shooters to enter the state, having paid gunsmith Charles Hummel of San Antonio the staggering price of $95 for it. The weapon helped to guard his Chihuahua-bound caravans until he replaced it with a more powerful .44-40 Model 1873 Winchester several years later.

Every man who lived or traveled on the Comanche-plagued Texas frontier came to value the repeater, although it could not always guarantee his survival. In September 1867, cattleman Oliver Loving and a companion were ambushed by Indians on the Pecos River as they scouted ahead of their trail herd. Loving had a Henry and his friend carried a Colt revolving rifle. Despite a mortal wound, Loving held the warriors at bay until help could arrive. Others were luckier. Prussian emigrant Jacob Huffman of Castroville, Texas, joined a posse in pursuit of Indian stock thieves and brought smoke on the band with his Henry when the pursuers caught up with them in the hills northwest of San Antonio.

Less savory citizens also favored the lever-action. "Old Man James" led a band of 25 outlaws on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River near Fort Griffin. Each man was armed with two Colts and a Henry. The brigands were finally dealt with by a mixed force of troops and settlers led by Colonel George Buell. The posse attacked the outlaws' stronghold in force and killed seven of them before the rest fled in defeat.

The Texas outlaws were small-time hardcases compared to another denizen of the Southwest. James Hobbs, a professional scalp hunter, carried two Henrys with him on his Indian expeditions in Arizona and Nevada. In an 1868 fight at Owens Lake, Nev., he and his companions drove in excess of 100 Paiutes into the water and killed more than half of them as they thrashed in the shallows.

The Henry proved equally popular on the Central Plains and in the Upper Missouri River country. When the Andrew Simmons party traveled down the Missouri by boat in 1866, it was threatened by a large party of Sioux on the riverbank. "Each of our Henry rifles contained sixteen cartridges when we opened fire:' exulted Simmons, "and the distance being about one hundred and fifty yards to the bluff, which was literally swarming with savages, not more than ten minutes elapsed until every one of them had disappeared. The fearful death howl, however, assured us that our fire had not been in vain."

|

|

The Sioux country continued to hear the Henry's voice as more of the weapons filtered upriver to the forts and trading posts. The celebrated Luther S. "Yellowstone" Kelly purchased a Henry carbineand stock of cartridges at Fort Berthold in Montana Territory in 1868 for $50. "With the Henry and the stubby little .44 caliber cartridges that went with it. "I killed many a buffalo, as well as other game, and it stood me in good hand when I was forced to defend myself in encounters with hostile Indians," Kelly wrote years later.

Kelly's carbine proved its value soon afterward when he contracted to carry the mail between Fort Berthold and Fort Stevenson. Ambushed by a pair of Sioux, he relied on the Henry to bring him safely through the encounter. At 30 yards one brave opened fire with a shotgun while the other lofted arrows at the dispatch rider. Kelly leaped from his horse and dropped the first Indian with a snap shot from the hip. The other sought cover behind a tree and they traded fire until one of the .44s broke the brave's arm. Clutching an arrow in his good hand, the Sioux rushed the courier, but the Henry put an abrupt halt to his attack.

Word of Kelly's encounter spread, and Colonel Regis de Trobriand recalled that Henrys became standard equipment for virtually all the mail carriers who served the Montana posts. Alexander Toponce, a contract freighter who hauled supplies to such isolated garrisons as Fort Union and Fort Benton, issued Henrys to his teamsters. In one fight with the Sioux, they held off several hundred braves and killed or wounded at least 50 with the blunt-nosed little .44 cartridges.

|

|

The Henry's reputation was such that even Army officers with ready access to government issue Spencers opted to purchase the civilian arm for their own use. Lieutenant A.H. Ward of the 36th Infantry served in Montana in 1866 and credited his Henry with saving his life in two near encounters. Lieutenant James A. Rothermel of the 8th Cavalry obtained a Henry while posted at Fort Boise, Idaho Territory, in 1868. His Henry was not so lucky for him as Ward's. While trying to club a rabbit with its butt, Rothermel jarred the hammer loose on a chambered round and mortally wounded himself.

The most prominent junior officer to carry a Henry was probably Lieutenant Frederick H. Beecher of the 3rd Infantry, a unit whose rank and file carried Spencer rifles. Beecher was photographed with some brother officers of the 7th Cavalry at Fort Wallace, Kan., in the spring of 1867, proudly holding his Henry. A year later he organized and led a company of picked volunteers against the Cheyenne in eastern Colorado. Most of the men carried Spencers, but there were a sprinkling of Henrys, and Beecher's repeater was probably in his hands when he was mortally wounded on an Arickaree River island that now bears his name in commemoration of the epic fight his command waged there.

In the late 1860s, the construction of a transcontinental railroad line brought thousands of men flooding into the high plains and mountain country beyond the Missouri, and, the Henry came with them in greater numbers. General Grenville M. Dodge, chief of the Union Pacific Railroad project, led a Henry-armed 1865 exploratory expedition into the Powder River country to chart a route for the rails and found a trafficable pass through the Laramie Mountains while his repeaters held the suspicious Cheyenne at bay. It was the start of an enduring partnership between the railroaders and the rimfires. Although the Army provided some troops to guard the construction crews, Indian attack was a constant problem, and the men often had to lay aside their tools and transits to mount watch with surplus Springfields and Spencers as well as the Henrys. Pioneer photographer A.J. Russell recorded the Union Pacific's westward progress in a series of remarkably clear and vivid pictures of the men and the harsh land they challenged. One image captured Engine No. 23 and its proud crew at Wyoming Station on a bright day in 1868. Gleaming with polish, and sporting a huge rack of elk antlers from its headlight, the locomotive and its tender were obvious objects of pride, much like the Henry rifle that one of the railroaders displayed for Russell's lens.

The construction crews and troops had to be fed, and this provided work for a legion of commercial hunters who killed buffalo by the thousand for their rations. One of the most prominent was Billy Comstock, who dropped the bison with his Henry by hunting them at the dead run while on horseback. He was bested only by William F. Cody, who preferred the more powerful .50-70 Springfield rifle to the light repeater. Cody and his Springfield, dubbed "Lucretia Borgia," once fired a match at Fort McPherson, Kan., with Lieutenant George P. Belden, who favored the Henry. Cody won $50 by beating the officer in 10 shots each at 200 yards. Belden then retrieved his cash by edging out Cody in a second shoot at 100 yards. He freely admitted that the Springfield had the reach on his .44.

The Indians also admired the brass-framed rifles, and they quickly acquired them by conquest or barter. The Cheyenne chieftain High Backed Wolf was carrying Henry No. 2729 when he was killed in battle at Platte Creek Bridge, Wyoming Territory, on July 25, 1865. In December 1866, the Sioux captured a brace of Henrys from two civilian scouts who were killed in the Fetterman Massacre near Fort Phil Kearney, another post in the territory. Capturing the repeaters in open battle was always a risky proposition, but sometimes the braves scored easy triumphs over tenderfeet, whose prudence was much less marked than their firepower. In 1868, a group of young Missourians set up a wood yard to supply riverboats with fuel as they made the runs up and downriver near Fort Union. An ostensibly friendly band of Sioux entered their camp and asked to inspect their Henrys. The greenhorns obliged and died under their own guns.

A large proportion of the Indian Henrys reached the tribes through trade, both legal and illicit. The post trader at Fort Bridget, Montana Territory, was selling .44 rimfire cartridges to the Shoshone as early as the fall of 1869, and he was but one of many who dealt in guns and ammunition in trade to the American Indians. So brisk was the commerce that the government felt obliged to exert some measure of control over it to prevent the hostiles from becoming too well armed. In November 1872, the chief Indian agent for Montana Territory, A.J. Simmons, issued a blanket ban on the sale of breechloading guns and ammunition to the Indians-which was cheerfully ignored by many merchants. By March 1873, the Piegan were acting restless and obtaining "all the 'Henry Rifles' and fixed ammunition possible," reported a nervous agent. Trader Nelson Story dealt extensively with the friendly Crow, and, in June 1873, reported that he had sold 2,000 rounds of Henry ammunition to them in the past six months. The Crow were blood enemies of the Sioux, so that ammunition probably went to benefit the whites; but there was still an alarming number of repeaters turning up among the hostiles.

James W. Schultz, a confirmed romantic, traveled up the Missouri in the 1870s to abandon his old identity and live among the Blackfeet, and found the Henry to be a very common arm among them. He was particularly impressed by William Jackson, a mixed-blood Blackfoot with Scot and French ancestry who carried a Henry as he scouted for the Army against the Sioux and led his own people against the enemy tribe. In one lone encounter with the Sioux he faced five warriors with his Henry and dropped three of them with dispatch in a running fight. The last warrior was spilled from the saddle at 100 yards in a piece of shooting that many trained marksmen might have envied. Jackson's Henry claimed more Sioux lives in June 1876 when he served with Major Reno's battalion of the 7th Cavalry at the Little Bighorn.

Despite the most diligent efforts to police the arms trade and keep the repeaters out of hostile hands, the treacherous commerce continued to flourish. As early as May 1871, General William T. Sherman was gloomily contemplating the situation in the Southwest, where "a system exists of trading the stolen horses & mules to Kansas & New Mexico for arms and ammunition for these marauding parties are all armed with Sharps, Spencer, and Henry Rifles, and are supplied with patent cartridges." Two years later a Crow warrior reported to an Indian agent that, during a fight with the Sioux on the Bighorn River, he concluded that "the Sioux must have good white men friends on the Platte and Missouri. They get...Winchester, Henry and Spencer rifles .... We took some of these guns from those we killed."

The rimfire cartridges used by the Henry were not intended for reloading, unlike the later stronger-cased .44-40 center fire rounds used in the Model 1873 Winchester (these had a replaceable primer in the center of the base). This fact did not deter the Indians from finding ways to use the expended cartridges again and again. A common method of reloading rimfire cases was to soak the heads off matches and cover the interior of the case's rim with the phosphorus, which, with luck, would give enough flash to detonate the powder when the hammer crimped the rim. It must have worked, for the Henry continued in use among the Sioux and Cheyenne well after the center fire arms became available. A survey of cartridge cases recovered from Indian positions at the Little Bighorn battle site registered the .44 rimfires as the second most numerous type at 380 cases, after the .45 Springfield carbine cartridges, which totaled 969. Some of the Henry cases bore two or three pairs of firing-pin indentations as proof of their reloading.

The Henry continued to serve with the Indians for more than 20 years of bitter strife on the plains and deserts of the West. The Apache were still using the weapon as late as the mid-1880s as they waged a final doomed campaign to reclaim their harsh homeland from white encroachment. The lever action endured among the frontiersmen as well. It was particularly popular in Mexico, where large government purchases of the Model 1866 Winchester, which used the old .44 rim, fire cartridge, ensured that ammunition would remain common for the earlier repeater for many years.

Probably the best testimonial to the durable Henry came from James H. Cook, a veteran of 40 years' experience on the frontier as a cowboy, Army scout and big-game hunter. For much of that period he relied on a Winchester or heavy .40-90 Sharps, but in the early 1870s, when he began his career in Texas, he trusted to Tyler Henry's handiwork. Cook signed on with cattleman Ben Slaughter's outfit near San Antonio while still in his teens. Slaughter was a Henry adherent, and the young greenhorn eagerly followed his example. "I had been at work but a short time when a Mexican rode into camp with an almost new Henry rifle on his saddle' wrote Cook in 1923. "He wanted to buy some cartridges for it. We had no Henry rifle shells, but did have some Spencer ammunition, and I succeeded in trading him, for his Henry, my Spencer carbine and what cartridges I had. In a short time I secured some ammunition for it from Mr. Slaughter. This rifle proved to be a most accurate shooting piece, and I had the satisfaction of knowing that nobody in Texas had a better shooting iron than I. " Many other men, from the Metis of Canada to the Yaqui braves of Chihuahua and Sonora, would have echoed Cook's praise of the handsome 16-shooter. With its elegant lines and commodious magazine, the Henry had proven itself to be a fit companion for those who dared "the drop edge of yonder.

Wayne. R. Austerman writes on many historical subjects and is especially interested in early arms. For further reading, try: The Story of the Soldier, by George A. Forsyth; The First Winchester, by John E. Parsons; Apaches and Longhorns, by William C. Barnes; and Yellowstone Kelly: The Memoirs of Luther S. Kelly, edited by Milo M. Quaife.

|

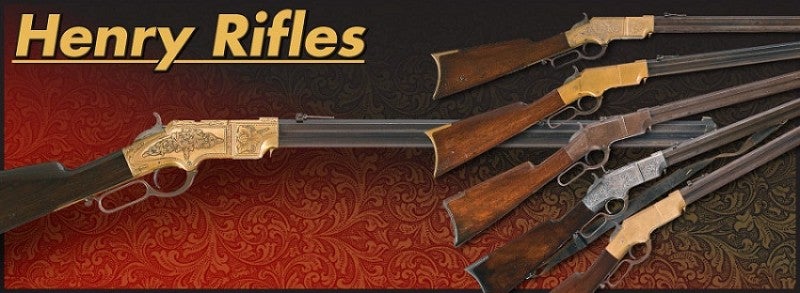

The Henry Repeating RifleVictory thru rapid fire

|

Chapter 1: The Henry is Born |

|

The Volcanic Repeating Arms Company began producing rifles and pistols in early 1856. These weapons used the "Rocket-ball" cartridge that consisted of a bullet with a hollow cavity in the base which contained the powder charge. A priming cap held the powder in place and provided ignition. This ammunition was a grossly underpowered round and was made in either .31 caliber or .41 caliber. Muzzle energy was not impressive, at only 56 foot pounds of energy.(32)

The frame of the Volcanic rifles were made of brass. Brass was easier to work with as well as not rusting as iron would. Pistols in .31 caliber were made in either 4 or 6 inch barrels holding 6 or 10 shots respectively. The .41 caliber pistol came with either a 6 or 8 inch barrel holding 8 or 10 shots. A Carbine was produced in 3 barrel lengths, 16 inches holding 20 shots, 20 inches holding 25 shots and 24 inches holding 30 shots. All of these were manufactured in .41 caliber. The ammunition was held in a tubular magazine beneath the barrel that was loaded from the top by pivoting the top few inches of the barrel housing.(32)

The Volcanic arms had several problems such as gas leakage from around the breech, multiple charges going off at the same time, and misfires. Misfired rounds would have to be tapped out with a cleaning rod as the gun had no means of extraction. The fact the "Rocket-ball" ammunition was too underpowered to be considered a hunting weapon or a man-stopper was another disadvantage. Two advantages the Volcanic carbines had was a rapid rate of fire and it's ammunition was waterproof.(32)

Oliver Winchester, the company's second president, was forced to use much of his private funds to keep the company afloat. However this did not last long. On February 18, 1857, The Volcanic Repeating Arms Company was declared insolvent. Its biggest creditor was Oliver Winchester. He was given the major assets of the company. Winchester then employed Benjamin Tyler Henry. On October 16, 1860, Henry was granted a patent for a new rifle and ammunition, patent number 30,446.(32) The 1860 patent had been assigned to Oliver F. Winchester but the guns were actually made by B. Tyler Henry at the company plant at 9 Artizan Street, New Haven, Connecticut on an inside contract basis. In the process, the basic patent of 1854, held by Oliver Winchester, was also utilized.(37)

The new ammunition consisted of a copper casing .875 inches long containing the priming compound in the rim. It used a 200 to 216 grain bullet and 26 to 28 grains of black powder. This gave a muzzle velocity of around 1125 feet per second. Not great but a far cry better than the old "Rocket-ball" round. The Henry round gave about 568 foot pounds of muzzle energy. The copper cases were head-stamped with the letter H for Henry.(8)

The gun itself held 15 rounds in a magazine beneath its 24 inch barrel. The rifle loaded by turning the top five inches of the barrel housing. This gun when fully loaded weighed in at over 10 pounds. The Henry was advertised as some sort of super weapon with capabilities of hitting targets at 1,000 yards. What this rifle could do is to fire rapidly. Forty-five shots per minute could be attained. In other tests 120 rounds could be fired in 5 minutes and 45 seconds.(14)

We now had a truly successful breech-loading repeating rifle. The improved design and better ammunition made the Henry a weapon to be considered for both hunting and as a man-stopper. All that remained was for the orders for these guns to come pouring in. The Civil War produced many orders to the New Haven Arms Company.

|

Chapter 2: The Henry Rifle In the Civil War

|

|

The Henry repeating rifle has had a very colorful past. It was the first of the repeating rifles that was truly successful. Part of this colorful past was born out of fire in the United States Civil War. The use of the Henry starts almost as soon as the opening shots of the Civil War. In 1860 there were 270 Henrys produced. Many of these found their way to the battlefields of the Civil War.(27)

The Henry did not become commercially available on a large scale until early 1862. Colonel Henry J. Hunt ordered Captain DeRussy to test the Henry. This test was conducted on November 19, 1861. It was reported to Colonel Hunt that the Henry would be a most useful addition to the weapons already in service.(14) One of these early Henrys was used by J. Marshall of Company G, 66th Illinois Infantry. He used an iron frame Henry serial number 147. This gun was manufactured in 1860.(15)

Another early Henry was used by J. Spangenberg of Company B, 3rd Regiment U.S.V. He used Henry number 1216. Louis Quinius of Company B, 66th Wisconsin Infantry used Henry number 8291. Matthew Brady is even credited with using Henry 8816. This is an engraved Henry and still supports its original sling. One of the earliest Henrys, serial number 6, was presented to President Abraham Lincoln. It is highly engraved, including his name on the right side plate and it is also gold plated. This Henry may be seen in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.(13)

The first Henrys appeared on the open market in Louisville, Kentucky by July of 1862. By the end of the year one dealer sold 500 Henrys. Other dealers selling Henrys in that year were located in St. Louis, Mo., Evansville, Ind., Peoria, Il., and Paducah, Ky. In 3 months over 900 Henrys were sold. According to the Louisville Journal of July 12, 1862, Henry rifles were offered for sale and in stock at James Low & Co's on Sixth Street, Louisville, Ky. Other Louisville dealers included Joseph Griffith & Son 5th Street, Dickson & Gilmore 3rd Street and A.B. Semple & Sons. Two Indiana dealers were Charles H. Bradford of New Albany and Wells, Kellogg & Co. of Evansville.(9) There were 3 known Henry rifle dealers in the East who represented the New Haven Arms Company. They were J.C. Grubb of Philadelphia, Hartley & Graham of New York, and William Reed & Son of Boston. On the west coast R. Liddle of San Francisco was offering Henrys.(13) In the Louisville Journal of July 14, 1862, it states that W.G. Stanton advertised the good qualities of the Henry. Henrys were offered for sale to both Unionist and Confederates.(14)

The retail cost of the Henry was set at $42.00 without the sling. Discounts were given to dealers purchasing a case of 10 Henrys, the discount being 20%. Rifle clubs purchasing a case of 10 received a 10% discount. Slings cost $2.00 extra, leather rifle cases were $5.00 and ammunition was $10.00 per 1,000, later increased to $17.50. Silver plating and engraving of rifles were an additional $10.00 and gold plating was $13.00 extra.(37)

The U.S. Navy also tested the Henry. Lt. W. Mitchell tested one on May 20, 1862. He fired 15 shots in 10 seconds. The rifle was fired 1040 times without cleaning. There were no major problems with fouling or functioning of the gun. He considered it the perfect weapon.(14)

"For time and rapidity, 187 shots were fired in 3 minutes 36 seconds. These were fired in rounds of 15 shots each, the actual time of firing only counted. One round (15 shots) was fired in 10.8 seconds; 120 shots were loaded and fired in 5 minutes 45 seconds. This includes the whole time from the first shot to the last ... 15 shots were fired for accuracy at a target 18 inches square, at 348 feet distance, 14 hit direct."(37)

"The firing was then continued to test endurance, &c., up to 1040 shots, the gun not having been cleaned or repaired from the first shot. The piece was then carefully examined, and found considerably leaded and very fouled, the lands and grooves not being visible. In other respects it was found in perfect order."(37)

Henrys were in use along the Mississippi River by 1862. John S. Tennyson, Pilot of the Gunboat Pittsburgh, states he had been using a Henry for a year. His letter to the New Haven Arms Company was dated October 17, 1863. That puts his purchase date in October of 1862. He also states that several others are armed with the Henry and wish to purchase ammunition.(14)

Also along the Mississippi River was a Henry used by Lt. Frank Church, U.S. Marines. He put his Henry to use against Rebel snipers along the riverbanks. He was assigned to command the Marines aboard the USS Black Hawk in 1864. He took part in the Red River campaign in March and his Henry was kept in constant use. Lt. Church was latter assigned to the USS Cricket where he was in charge of the Marines performing the same duty. Lt. Church's Henry preformed admirably.(10)

By November of 1862, several Kentucky regiments, U.S. and C.S., were using Henrys. By early 1863, other units including the Second Wisconsin Vol. Mounted Infantry, 23rd and 51st Illinois Infantry had armed themselves with Henrys. The 58th Indiana Infantry used their Henrys in the fall of 1863 at Chickamauga. One of these was owned by Sgt. Gilbert Armstrong of Company B.(9)

Henrys were ordered as far away as California. In May of 1863 one California dealer ordered 10 cases of Henrys. The demand for Henrys was high throughout the West. One dealer that helped to meet the demand was John W. Brown of Columbus, Ohio. He was located near the depot in the Rail Building.(7)

Brown also offered Henrys as "Slung" or "Plain." Slings were offered very early and were attached to the left side. Correspondence of October 1862 with John W. Brown shows that he returned to the factory for repair guns bearing the serial numbers 324, 359, 391, and 706. It is suggested they were to have sling swivels installed.(37) By January 28, 1863, Brig. General Alfred W. Ellet had witnessed one of the Henrys in action. He wished to obtain as many as 1,000.(14)

In a letter from Captain James Wilson of Company M, 12th Kentucky Cavalry written at Mumfordville, Ky., February 17, 1863, he describes his use of the Henry. He was attacked by 7 Rebels. With his Henry he killed all 7 with 8 shots. That would not have been possible with a muzzle loader. Captain Wilson also had a small skirmish with General John Hunt Morgan's cavalry in July, 1863. Wilson and his 67 men were attacked by 375 of Morgan's men. The fight lasted about 2 hours and a half. Wilson's men with their Henrys were able to drive Morgan's men over a mile, killing 31 and wounding 40. Wilson lost 6 killed and wounded. He states the Henry is the best gun in service. By October of 1863 the state of Kentucky would arm his entire command of 104 with Henrys.(37)

Governor Yates of Illinois armed some of the men from the 64th Illinois Infantry, also known as Yates' Sharpshooters, with Henry rifles. One rifle, serial number 3183, was shipped from the factory in 1863 by the Adams Express Company to Illinois. This Henry was used by a member of Company G. Many of the men of the regiment purchased their own at a cost of $41.00. Many of these Henrys were put to good use during the campaign for Georgia. It is also interesting to note that the 64th and the 7th Illinois Infantry units took part in the Grand review of May 19, 1865. The men attracted special attention with their unique brass frame 16 shooters and received frequent cheers. Another Henry of the 64th's was serial number 4944. It is engraved, Nicholas Ham Co F 64th Ill.(15)

Henrys were also offered for sale in Virginia. Some time before September, 1863, Messrs Adams of Wheeling, Virginia sold a Henry to John Brown who was a Lieutenant of Company C 23rd Regiment of Illinois Volunteers. He in turn wrote to the New Haven Arms Company requesting 15 to 20 more Henrys to be purchased by his men.(14)

R.K. Williams writes on March 3, 1863 of witnessing the use of Henrys in Kentucky. He feels that the Henry is the most effective weapon in use. He states that Colonel Netter of the Kentucky Volunteers at Owensboro, Ky. was attacked by 240 Rebels. He had 15 men armed with Henrys and not only were able to defend themselves but drove the Rebels from the field.(14)

John H. Ekstrand, Regimental Ordnance Sergeant of the 51st Illinois Volunteer Infantry used his Henry as well as others in his unit at the Battle of Chickamauga. Sergeant Ekstrand had purchased his Henry from Bowen in Chicago sometime before September, 1863. He would also purchase another 10 Henrys at a latter date for other members of the 51st Illinois.(14)

The 10th Michigan Cavalry was armed in part with Henry repeating rifles. A part of Company B was detailed to guard McMillian's Ford on August 24, 1864. Colonel Trowbridge gives this account of the action. "Eight men were sent to guard McMillian's Ford, on the Holston; one of them went off on his own hook, so that seven were left. One of them was a large, powerful fellow, the farrier of company B, by the name of Alexander H. Griggs, supposed to belong to Greenfield, Wayne county. These seven men actually kept back a rebel brigade from crossing that ford for three and a half hours by desperate fighting, killing forty or fifty. The rebels, by swimming the river above and below the ford, succeeded in capturing the whole party. During the fight this big farrier was badly wounded in the shoulder. "General Wheeler was much astonished at the valor of these men, and at once paroled a man to stay and take care of this wounded man. Approaching the wounded farrier, the following dialogue is said to have taken place: "General Wheeler. Well, my man, how many men had you at the ford? "Griggs. Seven sir. "Wheeler. My poor fellow, don't you know that you are badly wounded? You might as well tell me the truth; you may not live long. "Griggs. I am telling the truth sir. We had only seven men. "Wheeler (laughing) Well, what did you expect to do? "Griggs. To keep you from crossing, sir. "Wheeler. Well, why didn't you do it? "Griggs. Why, you see, we did until you hit me, and that weakened our forces so much that you were too much for us. "Wheeler was greatly amused and inquired of another prisoner (who happened to be a farrier too), 'Are all the 10th Michigan like you fellows?' 'Oh no!' said the man, 'we are the poorest of the lot. We are mostly horse farriers and blacksmiths, and not much accustomed to fighting.' 'Well,' said Wheeler, 'if I had 300 such men as you I could march straight through h--l."(59)

The largest privately funded Henry regiment was the 7th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. They were armed with over 500 Henrys which they purchased at $52.50 each.(36) The second largest privately funded Henry regiment was probably the 66th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. They purchased over 220 Henrys.(38)

The Henry was an expensive weapon that most soldiers could not have afforded at $52.50. That is almost 4 months pay for the Civil War solider. It does not seem likely that he would be able to save that much money for the price of a Henry rifle, no matter how good a weapon it was. Most of the units that bought their own Henrys purchased them in late 1863 or early 1864. The answer to where they got the money to purchase their Henrys lies in a law passed by the government, the Veteran Volunteer Act. This act gave to the solider, upon re-enlisting, a 30 day furlough and more importantly a $400.00 bounty. This was about 3 years salary to most. Indeed it was a lot of money. Upon returning to active duty they would be able to spend $52.50 for a weapon that would help save their lives. Henrys were in short supply but the 7th and the 66th Illinois Veteran Volunteers were fortunate in purchasing enough to arm their regiments.(61)

It is interesting to note most of the Henrys used in the Civil War were privately purchased. The prices ranged from as low as $36.00 to $80.00 for the top end. One rifle, serial number 4178, is inscribed: G Burkhardt, Co H 7th Ill Vol Inf.(6) This rifle was produced in early 1864. The 7th Illinois Infantry took part in several battles with their Henrys of which most of the men had purchased theirs by September, 1864.(11) The 7th Illinois Infantry took part in the defenses at Allatoona Pass, Georgia. There they had 191 Henrys. The 7th Illinois fired over 31,000 rounds of ammunition from their Henrys.(36) Major William Ludlow gives us his account of the Battle of Allatoona Pass: "What saved us that day was the fact that we had a number of Henry rifles. These were new guns in those days and the commander had held in reserve a company of an Illinois regiment that was armed with them until the final assault should be made. When the artillery reopened this company of 16 shooters sprang to the parapet and poured out such a multiplied, rapid, and deadly fire that no man could stay in front of it, and no serious effort was thereafter made to take the fort by assault." The 7th Illinois' flag was also a target of many a Reb. It sustained 217 bullet holes and the staff was hit 11 times.(13) Probably the best Civil War picture of Henrys is that of the 7th Illinois Infantry's Color Bearers and Guard. It was taken sometime in late 1864 or early 1865. It shows 11 members of the 7th Illinois of which 6 are armed with their Henrys, 1 is a drummer, the Sergeant-Major has an 1833 Dragoon saber, 2 are flag bearers and 1 officer in charge.(13, 16)

The 7th Illinois Infantry got their Henrys as a result of Captain John Alexander Smith's efforts tracking down enough Henrys for sale. "He applied for an order to go to Hartford, Connecticut to get the rifles. It was refused. He then secured a leave of absence and paid his own expenses. Arriving in Hartford, he found no rifles, but information that 500 of them had been shipped to Chicago. Smith telegraphed to hold the rifles, and took the first train for Chicago. He found the rifles, but had to pay $52.50 for them instead of $47.50 each. He paid this difference out of his own pocket, and has never been reimbursed to this day. He ordered the rifles shipped by express, and started South. At Cincinnati he found the Captain of a company that was raised in his native town in Ohio. Going with him to see the boys of the company, he was stopped by a large van unloading some big boxes into a warehouse. Looking at the boxes he was astonished to see them directed to Captain J.A. Smith, 7th Illinois Infantry. 'What are you doing with those boxes?' he inquired. 'Storing them; no express matter sent South unless prepaid. 'Captain Smith borrowed enough money from his friend, with what he had, to prepay the freight, and the guns were forwarded. As soon as the balance of the regiment saw the sixteen-shooters, they all wanted them. The whole 500 were purchased. They arrived at the regiment a few days before the Allatoona fight. Now, the concurrent testimonies of the Union and Confederate forces agree that the 16-shooter rifles were all that saved the day in that terrible October battle."(36)

Another unit to have several Henrys was the 23rd Illinois Infantry. Lt. Colonel S.A. Simison, the commanding officer, in a letter dated February 25, 1865, to the President of the New Haven Arms Company wanted to know at what price he could arm his entire battalion with Henrys. He also stated that he purchased 50 Henrys in the winter of 1863. In using these 50 Henrys, Colonel Simison was able to judge the effectiveness of the Henrys and making the decision to seek to arm his command.(14)

The government did purchase 1731 Henrys. These were issued solely to the 1st D.C. Cavalry. The first government purchase was from Merwin & Bray of New York for $42.00 for one Henry. The first substantial purchase came on July 23, 1863 from the New Haven Arms Company in Connecticut. This purchase was for 241 Henrys at a cost of $36.00 each. Other purchases followed: September 19, 1863 for 1 Henry, October 31, 1863 for 60 Henrys, March 9, 1864 for 800 Henrys, June 17, 1864 for 1 Henry, April 19, 1865 for 500 Henrys and the last purchase was made on May 23, 1865 for 127 Henrys. The number of Henrys purchased during the war amounted to 1104 with the rest of the 1731 being delivered after Lee's surrender. For the larger quantity orders the government paid $36.00 per Henry. The Henrys purchased in 1863 by the Ordnance Department are found in the serial number range of 3,000 to 4,200.(7)

As mentioned the government issued these Henrys to the 1st D.C. Cavalry. They were eventually completely armed with Henrys. This regiment was commanded by Colonel Lafayette C. Baker. This was a special duty unit assigned to provost duty. It was also known as "Baker's Mounted Rangers." In May, 1863 they were assigned to General Kautz's cavalry division. This regiment fought in several engagements which included: Weldon Railroad Station, raids in southern Virginia, Battle of White's Bridge, Ft. Pride, Petersburg, Reams Station, Roanoke Bridge, Deep Bottom, Cox's Mill, 2nd Reams Station, Sycamore Church, Darbytown Road, and many others.(22) Colonel John T. Wilder in a letter dated March 20, 1863 wanted to order 900 Henrys to arm his command. However, the New Haven Arms Company was unable to deliver the order. Wilder purchased the next best thing to a Henry, a Spencer.(14)

It seems that soldiers from Illinois purchased several Henrys. Here are a few more of their purchases in addition to the ones already mentioned. Serial number 2779 was used by John Cowens of Company D, 23rd Illinois Infantry. Serial number 1692 and 2523 were used by members of the 66th Illinois Infantry as well as number 2575. This last one was owned by Lorenzo Baker of Company D. It is a highly engraved Henry. Serial number 2639 is inscribed Chas Webster Co D WSS Vet. Vol. Gil Harbison of the 73rd Illinois Volunteer Infantry used a Henry at Spring Hill and Franklin, TN. Part of the 85th Illinois which was part of the 3rd Brigade which consisted of the 52nd Ohio, 86th Illinois, 110th Illinois, 125th Illinois and the 22nd Indiana all armed themselves in part with Henrys at their own expense. Christopher C. Cowan of Company K of the 96th Illinois Volunteers used his Henry effectively at Chickamauga until he was shot on September 20, 1863. The 115th Illinois Volunteers list 2 Henrys at least, serial number 6639 and 6400 which belonged to Captain Hyman of Company D.(15)

Other users of Henrys involve those used by the Confederacy. A large number of Henrys were captured or privately purchased by the South. Many people today have questioned the use of Henrys by the Confederacy. The fact remains they were used by the Confederacy. There are no records of sales that were made to the Confederate government, but Confederate troops did purchase Henry rifles. Louisville, Kentucky was a place where all kinds of arms were for sale. Most of the Henrys used by the Confederacy were captured from the Union. Several captured Henrys were stamped at Confederate armories, with the "C.S.A." indicating inspection. Some captured guns were marked "CS" or " CSA" indicating a loyal Southerner wishing to establish the fact that the gun was used against Yankee troops in battle.(35)

Henry rifle number 287 was used by William S. Skelton a lieutenant in Company E of Stirmans 1st Arkansas Cavalry, CSA. This gun was manufactured in 1861. A picture of this gun is in the Winchester Book on page 46. It is one of the first Henrys used in the war by either side. The fact that Skelton was a Confederate makes it even more unique. This particular Henry was offered for sale a few years ago in Shotgun News at the price of $50,000, making it one of the most expensive Henrys.(3) Lieutenant Skelton was promoted from the ranks to Lieutenant on July 10, 1862. Stirmans 1st Arkansas Cavalry was formed by consolidation of the 1st Battalion Arkansas Cavalry and the Bridge's Battalion of Sharpshooters, CSA. They fought in many battles, one being Corinth, Mississippi on October 3 to 5, 1862. At this battle Lieutenant Skelton was killed.(6) Skelton's Henry was recovered by a Minnesota regiment. The use of this Henry for the rest of the war is unclear.(3)

Skelton's Henry was not the only Confederate Henry to be used in 1862. Captain Loenzo Fisher of the 10th Kentucky Partisan Rangers was also armed with a Henry rifle. He is even pictured with his Henry in the book The Partisan Rangers of the Confederate States Army. He did most of his fighting throughout Kentucky. Others in his command were probably armed with Henrys but it is not known how many. He died sometime in late 1862.(12) The 7th Virginia Cavalry was also armed with Henrys. It is stated that the 7th Virginia Cavalry used their Henrys at the battle of Reams Station.(1) It is interesting to note that the 1st D.C. Cavalry was also at Reams Station.(2) Reams Station is one of the few battles in which part of both sides were armed with Henrys.

The 7th Virginia Cavalry got their Henrys from the 1st D.C. Cavalry by capturing several at Stony Creek, Virginia on June 24, 1864. Another 200 Henrys were taken from the 1st D.C. Cavalry on September 15, 1864 at Sycamore Church. These were issued to the 11th, 12th, and 35th Virginia Cavalry units.(7) It leads one to wonder about the 1st D.C. Cavalry as a fighting unit. Many testimonies have been given concerning the Henrys regarding the fact that a man armed with a Henry could take on 4 or more of the enemy. Major Joel W. Cloudman of the 1st D.C. Cavalry even mentions this in his testimony on the Henry after the Battle of Reams Station on August 24 and 25, 1864. On March 31, 1864 the 1st D. C. Cavalry were issued 783 Henrys and on June 30, 1864 they were issued another 639 for a total of 1422 Henrys.(7) (These figures do not match up with the government purchases given in another source.) That many Henrys, firing at a rate of 32 shots per minute, should have been able to produce a volume of fire equal to 227,520 rounds in five minutes. That even includes reloading time. The question is, how can a force armed with 1422 Henrys lose so many of them? It seems the 1st D.C. Cavalry was the best supplier of Henrys and ammunition to the Confederacy. Captain Jesse McNeil's Rangers were also armed with Henrys. The Rangers used their Henrys to capture major General George Crook and Major General Benjamin F. Kelley on February 21, 1865 at Cumberland, Maryland.(7)

One of the last Henrys to be used by the Confederacy were those given to Jefferson Davis' bodyguards. These accompanied President Davis on his flight from Richmond in April, 1865. One of these Henrys is pictured on the cover of Civil War Times in the September, 1982 issue.(5) The following paragraphs show a few more Henrys that saw service in the Civil War. Serial number 1,639 was used by Asahel Horton who enlisted in the "Western Sharp Shooters" which became the 14th Missouri Infantry and then the 66th Illinois Infantry. This unit fought with distinction throughout the Atlanta Campaign and Sherman's March to the Sea. He became a corporal and reenlisted December 24, 1863. He served until he was mustered out July 7, 1865.(37)

Michael G. Buzard enlisted August 12, 1861 from Oregon, Missouri and used Henry number 4,434. He became a sergeant in Company F of the 25th Missouri Infantry. The regiment consolidated February 4, 1864 with Bissell's "Engineer Regiment of the West" as the 1st Missouri Engineers. He served in Company H and after October 31, 1864 in Company D. He also served with General Sherman on his March to the Sea. Michael was discharged July 22, 1865.(37)

Henry number 3,347 has the inspector's initials "C.G.C." This Henry is one of the 800 ordered by the Ordnance Department March 9, 1864 for the 8 new companies of the 1st D.C. Cavalry, transferred in August, 1864 to the 1st Maine Cavalry.(37) Serial number 2,710 appears to be a captured Henry. Scratched on the left side plate is: "Captured at/ Goodrich's Landing/ Oct 1864/ IGS." On the right side plate are the initials "GMS" and the date "1868." In October of 1864, Goodrich Landing on the Mississippi River was a Union supply base.(37) Wilber F. Lunt enlisted in the lst DC Cavalry February 11, 1864, from Biddeford, Maine. He became a corporal in Company I and later a sergeant in Company K on December 12, 1864. On June 20, 1865 he became lst sergeant of Company G, lst Maine Cavalry. He used Henry number 1,434. On September 16, 1864, his company was engaged with Confederate cavalry at Sycamore Church, VA, where Lunt evaded capture by climbing up a tree.(37) Henry number 9,223 was used by a member of Company E of the 2nd Pennsylvania Reserve Volunteer Corps, known as the 31st Penn. Infantry. This unit was recruited in Philadelphia and fought in the Peninsular Campaign, at Second Bull Run, Antietum, Fredericksburg and Gettysburg. This Henry is engraved "Arch McAlister" "CoE. 2nd Regt, P.R.V.C." "Enlisted April 27th 1861". "Discharged June 16th, 1864".(37) Another early Henry was serial number 976. This Henry was used by A. W. Morris of Co. D. 16th Ill. Vet. Vol. Infantry, 1st Brigade, 2nd Division./14th Army Corps. He enlisted June 25th 1861 and reenlisted December 22, 1863. He was discharged July 17th, 1865. Alfred W. Morris was from Hannibal, MO, and served with the 16th Illinois through the Atlanta Campaign and Sherman's March to the Sea. The 16th Illinois was the first regiment to enter Savannah and also fought at Bentonville, NC.(37) Lucius P. Tallman enlisted in the "Western Sharp Shooters," the 66th Illinois Infantry, and used Henry number 2,582. His enlistment date is November 5, 1861 from Stillwater, Minn. He reenlisted December 24, 1863 and was mustered out July 7, 1865. The 66th Illinois Infantry had over 220 Henrys that their members purchased at their own expense. These Henrys were used effectively against Joe Wheeler at Snake Creek Gap, Georgia on May 9, 1864.(37) Another interesting Henry was one owned by Major General James G. Blunt. His is serial number 2,378 and is gold-plated with a rosewood stock. His name is engraved on the right side of the breech opening, "Major General J.G. Blunt." Major General Blunt was the Union general commanding volunteers in the district of the Frontier in Southern Kansas and the Indian Territory. In October, 1863 he barely escaped an ambush by Quantrill at Baxter Springs.(37)

The 58th Indiana Infantry also used several Henrys. Henry number 2,347 was used by John F. Philips who enlisted in Company C November 12, 1861 from Potoka, Indiana. He was mustered out July 25, 1865. The 58th Indiana Infantry fought in several campaigns including Chickamauga and Knoxville in 1863 in the Atlanta Campaign the 58th took charge of pontoon trains and in Sherman's March to the Sea built bridges and repaired roads. John Fox was in the same company and used Henry number 2,293. Sergeant Gilbert Armstrong was presented a Henry by his friends for his bravery at Stone's River. Armstrong was wounded at Chickamauga and his Henry was captured by the Confederates.(37)

Two other Henrys used in the Civil War were serial number 504 and 8,051. Number 504 was used by F.W. Binger at Salt Creek, Nebraska in 1864. Henry 8,051 was used by Frank W. Meese. Gideon Welles, Sec. of the Navy was presented serial number 9, a highly engraved Henry. Edwin Stanton, Sec. of War, presented an engraved Henry, number 2,317, to Governor W.F.M. Army of New Mexico in August of 1863.(37)

It is safe to say that Henrys were used throughout the Civil War and in all theaters of the War, from 1862 to 1865. Most of the early purchases were made in the West. While in the east the 1st D.C. Cavalry was fully armed with Henrys by June of 1863. During the Civil War over 10,000 Henrys were used. These were mainly privately purchased Henrys.

The government purchased 4,610,400 cartridges for the Henrys.(27) There were also many private purchases of ammunition. At the Battle of Bentonville, NC the 7th Illinois Volunteer Infantry shot up so much ammunition during the night, the Confederates were gone the next morning.(11) They thought the entire Union army had arrived.

One very interesting Henry appeared for sale in The Shotgun News September 1, 1990. It is an extraordinary Civil War presentation engraved Henry. It is inscribed to "Sgt. Edgar Putnam, 9th N.Y. Cavalry." Putnam was awarded the Medal of Honor for distinguished Valor at Crump's Creek, Virginia May 27, 1864. The asking price was $135,000.(4) That is one of the highest asking prices for a Henry. Most Henrys sell for between $6,000 and $15,000.

The Henry changed warfare, but the military was slow to catch on. The Henry proved that a frontal assault against a smaller force armed with repeaters was doomed to failure. However frontal assaults were still made in World War I with disastrous results.

The Battle of Allatoona Pass

The Battle of Allatoona Pass is the one battle where the Henry Repeating Rifle played a very important role. Some even credit the Henry with winning the battle. Captain John A. Smith of Company E, 7th Illinois Infantry even states that the success of this battle would decide whether the march to the sea would be possible or not. Was Allatoona Pass an important battle? Of the 128 volumes of the "Rebellion Official Records," there are 2 volumes practically devoted to events leading up to this battle, the battle itself, and the consequential results.(51) It was important for many reasons but most of all it was General Sherman's supply line. The Western & Atlantic Railroad was used to ship supplies to Sherman's army during the Atlanta campaign. So Allatoona Pass was a supply base that contained over 1,000,000 rations, including 8,000 beef cattle, and ammunition. It also contained over $3,000,000 worth of property. This made Allatoona Pass a likely target for General Hood.(57)

Colonel John T. Tourtellotte was the garrison commander. His troops consisted of the 4th Minnesota Infantry, the 18th Wisconsin Infantry, the 93rd Illinois Infantry, part of the 5th Ohio Cavalry and the 12th Wisconsin Battery. His total command numbered 985. The artillery consisted of 2 Napoleons and 4, 3 inch rifles. The defenses were 2 small forts, a trench works and several small redoubts and rifle pits.(57)

Major General Samuel French was given the job of securing Allatoona Pass and burning the railroad trestle over the Etowah river. This order was sent to French October 4 at 7:30 a.m. French was also to fill in the railroad cut at Allatoona Pass. This, if it could be done, would be a major undertaking. The cut itself was 300 feet long and varied in depth up to 175 feet. This was to be filled in with anything available including dirt, logs, brush, rails, etc.(57) General Hood stressed the burning of the bridge and even sent a second message stressing its importance. The number of French's troops seems to very from 3,200 to as high as 6,000 depending on what source you read. French was also given a Battalion of 12 Napoleons commanded by Major John Myrick. It is thought that General Hood did not know about the rations located at Allatoona Pass. Had he known he might have made more of an effort, making it a top priority mission.(57)

On October 4, 1864, General Sherman telegraphed General John Corse, age 24, at Rome to take his entire command to Allatoona Pass, having learned that Confederates were heading that way. General Corse left Rome at 8:30 PM on October 4 and would not arrive at Allatoona Pass until 12:00 midnight on Oct. 5. Because of a train mishap he was only able to transport 1,054 men. These troops included: 8 companies, 280 men of the 39th Iowa commanded by Lt. Col. James Redfield, 9 companies, 267 men of the 7th Illinois commanded by Lt. Col. Hector Perrin, 8 companies, 267 men of the 50th Illinois commanded by Lt. Col. William Hanna, 2 companies, 61 men of the 57th Illinois commanded by Capt. Van Steenberg and a detachment of the 12th Illinois 155 men commanded by Capt. Koehler. This brigade was commanded by Colonel Richard Rowett.(43) It should also be noted that Company D of the 7th Illinois was left behind in Rome as part of the guard, each regiment was required to leave one company.(44,51) Upon arrival at Allatoona Pass General Corse unloaded his troops and 165,000 rounds of ammunition. He sent the train back to Rome for the rest of his troops but another accident prevented there arrival in time for the battle.(43)

On October 3 almost every dispatch sent by General Sherman to his generals included some mention of Allatoona Pass. General Corse's chief objective was to prevent the enemy from taking Allatoona Pass. To accomplish this he had a total force of around between 1,500 to 2,000. This included his own force of 1,054 and those of Col. Tourtellotte, about 1,000. At 6:00 AM on October 5, General Corse's troops were posted as follows: The 7th Illinois and 39th Iowa were in line of battle, facing west on a spur that covered the redoubt on the hill over the cut; one company of the 93rd was in reserve. The balance of the 93rd was deployed as skirmishers and moved along the ridge in a westerly direction feeling out the enemy who was trying to push around the right flank. The 4th Minnesota and the 50th Illinois and 12th Illinois were in the works on the hill east of the railroad cut. The balance of the troops were on outpost or skirmish duty.(43)

At 6:30 a.m., the Confederate artillery on Moore's Hill opened fired on Union positions. The 12th Wisconsin Artillery answered and an artillery duel was under way. French ordered General Claudius Sears to continue toward the railroad and attack from the north. At the same time General Francis Cockrell with 1900 troops would attack, supported by General William Young with his 400 troops, the western most end of the Union lines.(57) This is the position defended by Company E of the 7th Illinois.

At 8:30 AM from the north on the Carterville Road General Corse received the following demand of surrender under a flag of truce. For a flag of truce a black servant had a handkerchief stenciled with the words "A. Coward" on it. French's adjutant, Major David Sanders, handed the surrender demand to Lieutenant William Kinney of the 93rd Illinois saying he would wait 15 minutes for a reply.(57) Lt. Kinney gave the note to Colonel Rowett who delivered it to General Corse. The note read:

"Around Allatoona, Oct. 5, 1864

Commanding Officer U.S. Forces, Allatoona;

Sir:-I have placed the forces under my command in such position that you are surrounded, and to avoid a needless effusion of blood I call upon you to surrender your forces at once and unconditionally. Five minutes will be allowed you to decide. Should you accede to this you will be treated in the most honorable manner as prisoner of war. I have the honor to be, very respectfully,

S.G. French, Major-General commanding"

To this surrender demand General Corse replied the following:

"Headquarters, Fourth Division, Fifteenth Army Corp.

Allatoona, Ga., October 5, 1864, 8:30 a.m.

Major-General S G French, C.S. Army, etc.:

Your communication demanding surrender of my command I acknowledge receipt of and would respectfully reply that we are prepared for 'the needless effusion of blood' whenever it is agreeable to you. I am, very respectful,

Your obedient servant,

John M. Corse, Brigadier-General

Commanding U.S. Forces"(42)

Upon delivering his answer General Corse prepared his defense. He directed Col. Rowett to hold the spur on which the 39th Iowa and 7th Illinois were formed, sent Col. Tourtellotte over to the east hill with orders to hold it to the last, sending for reinforcements if needed. Taking 2 companies of the 7th Illinois down a spur parallel with the railroad and along the brink of the cut, so disposed them as to hold the north side as long as possible. Three companies of the 93rd, which had been driven in from the west end of the ridge were distributed in the ditch south of the redoubt, with instructions to keep the town well covered by their fire and watch the depot where were stored over a million rations. The remaining battalion, under Major Fisher, lay between the redoubt and Rowett's line, ready to reinforce whenever most needed.(43)

Just after issuing these orders the attack came full force. Young's brigade of Texans, 1,900 strong, had gained the west end of the ridge and moved along the crest striking Rowett's command. They were checked by the massive fire of the 16 shot Henry repeaters. The 7th Illinois continually raked the Confederate lines firing as fast as they could work the levers on their rifles, cutting the Confederates to shreds with their sixteen shooters. These repeaters would be used many time throughout this battle checking the Confederates in at least 6 attacks on their position.(43)

An eye witness account is given by a member of Company A, Private Frank D. Orcutt. First off Orcutt enlisted at the first call for volunteers in Company K. After the 3 month enlistment was up he re-enlisted into Company A for 3 years. The date of this enlistment was July 25, 1861. Orcutt was from Carlinville, Illinois and is listed as a musician in the company roll. He re-enlisted as a Veteran on Dec. 22, 1863 and fought the rest of the war, mustering out July 9, 1865.

His account of his actions is taken from letter written by Frank D. Orcutt home. "Early in the forenoon of the next day a demand came in for a surrender followed immediately by an impetuous and headlong attack which overwhelmed Company I who were out as Skirmishers, killed the Capt. Jack Sullivan and captured all who were not killed. The assault partially succeeded. The 7th Regt. and 39th Iowa were partly cut off from the fort, but those who reached it poured in the severest fire upon the assailing forces that had ever been seen up to that time, with such splendid result that the attacking forces melted away out of sight as though the earth had opened and swallowed them. The cook of Company A, who had coffee made for us in a ravine near us was taken prisoner, but in the confusion and haste of leaving, the Rebels neglected to take him along. He says General French with an entire division were the assailants. That he saw the General make frantic endeavors to induce his men to storm us out. He saw them make several attempts to rout us, each time resulting in a sudden collapse of their line when they would come tumbling back to the starting place to receive the scolding of General French who upbraided them for their failure to dislodge us from the ditch outside the fort. Have accord the opportunity of an ocular demonstration of the effectiveness of the writer's firing, after fully 400 cartridges had been used without any perceptible result--besides burning his hand and exhausting and depressing him mentally and physically. It was at the close of the battle the writer had climbed over the top of the fort and was looking over the top of a six pounder cannon where a fellow in gray bending low came up from a ravine and entered the cabin of an artillerist. Soon smoke issued from a knothole of the side toward us. Levelling my 16 shooter across the wheel of the open carriage I awaited a 2nd discharge from the hole. As rapidly as his gun could be loaded, for it was an Enfield Rifle (muzzle loading) he proceeded with his 2nd shot. Instantly my rifle cracked for my aim had been fixed upon the hole and no more smoke issued from that place. Almost immediately from behind a tree close to the cabin a glimpse of a hat was had. Then it disappeared only to reappear in a moment. My gun was already in position having good rest over the open carriage and at the second appearance of the head, was discharged. I was positive that from my high position none other observed the hat, and not another shot was fired from the fort that day afterward. Our cook came in and reported the enemy as retreating, and upon going to the spot from curiosity, a body was seen lying in the shanty, and one at the foot of tree. Both killed by a bullet in the head. There are no grounds for believing that any other of the many shots fired by the writer took effect. Therefore his service to the Government is no longer to be considered as non-effectual. With a range inside of 60 yards and no distracting movements to interfere it will readily be seen and recognized as no very skillful performance, yet large numbers of men go into battle and do valiant service without ever knowing if they ever succeeded in producing even a scratch upon their opponents."(60)

Up from the west and the south Young's troops came. They were headed towards the warehouse containing the rations and army supplies. Capt. John A. Smith, who was only about 20 years old, was commanding Company E of the 7th Illinois Infantry. This company had 52 men and was the largest company in the 7th Illinois Infantry at this time. He was asked if he could take care of the attacking regiment, part of Young's brigade, numbering about 400 troops. He replied, "I can, Sir," and with a sixteen shooter on his shoulder he turned to his 52 men armed with Henrys also and said "Come on, boys" and gave the command, Forward. The movement was in the open. The enemy could not understand it, 52 against 400. Reaching a position in line with the left flank of the rebel regiment, Capt. Smith gave the command, "By right into line." In 5 minutes the rebel regiment was broken to fragments and practically annihilated. The huge volume of fire pouring forth from the Henry Repeating tore the rebel regiment to pieces. This was not without a price to pay. Company E lost 17 killed, 21 wounded and 4 captured. This was 80% of the company's strength.(42)

Captain Smith states in 1910 his account of this action. He mentions that the Henry Repeating rifle played a crucial role in saving Allatoona Pass form the rebels. Captain Smith was the person that purchased the Henry rifles for the 7th Illinois Infantry. When he bought them, the agent in Chicago from whom he purchased them made Captain Smith a beautiful silver mounted presentation grade Henry with his name engraved on the breech. This Henry accompanied him to Allatoona Pass. It was the only time in which Captain Smith used a gun in the line of battle.(51)

In the 2 hour action in which Company lost 80% of their strength, Captain Smith used his silver plated Henry, firing and reloading many times. The following is Captain John A. Smith telling what happened to his silver plated Henry. "I had a boy in my company named William H. Burwell. He was a very large man, not very tall, and on the left of the company. We would wait until we heard the rebels yell as they came up to the side of the ridge. They always yelled first and then fired. When we were reloading after one of these volleys, Burwell turned to me and said, "Captain, my gun is out of order.' He couldn't get the cartridge into the chamber. Meantime I had loaded and emptied my gun several times. I said, 'All right Billie. You take my gun and I will see if I can do anything with yours.' I got down on my knees and got out one of those Barlow knives which you all remember, but I was unable to remove the difficulty."

"About that time we were ordered back to the fort and after the battle was over next morning we commenced gathering up the dead. Of course the wounded and dead lay all together that night. The left of the company rested on the Carterville Road. In one of the ruts that had been worn by the wagons lay William Burwell on his face, dead, and under him was my silver mounted rifle all covered with blood. He had evidently been killed in the act of firing. My gun was the only one saved out of the 17 lost by the company."(51) The Confederates ended up with the rest. As long as the ammunition held out, they were of use to the Confederates. General French even kept a captured Henry from Allatoona Pass. He surrendered the brass frame Henry shortly after the surrender of Lee at Appomattox.(58)

Because of the action of Company E and the 7th Illinois Infantry with their Henrys, Allatoona Pass was saved from the Confederates. Company E was shot to pieces and along with the rest of the 7th Illinois, the 93rd Illinois and the 39th Iowa fell back to the fort.(51) It was now about 11:00 a.m. By this time the Confederates had driven most of Corse's command into the forts on either side of the railroad cut.(57) For the next 2 and a half hours they repelled several attacks from the north, the west, and the south from Young's, Sear's and Cockrell's brigades. During this action Col. Redfield of the 39th Iowa fell, shot 4 times.(51) General Young was also wounded, receiving a nasty wound to the foot.(57) During this fighting a lot of it was cruel hand to hand fighting. Bayonets and rifle butts were used to fight off the attackers. Every man in the 39th Iowa Color Guard was killed or wounded and their flag was ripped from the staff.(57)

The Confederates were so disorganized by now that no regular assault could be made on the fort. The trenches were filled and the parapets lined with men. As long as the ammunition held out the fort was impregnable. The fort was receiving fire from the north, south and west. An effort was made to take the U.S. fortifications, but the 12th Wisconsin battery was able render it impossible for a column to live within 100 yards of the works.(43) After several cannoneers had been wounded, private James Croft loaded one of the 3 inch-guns with double canister and fired. This shot demolished the Confederate ranks attacking the high ground west of the fort. For this action he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.(57)

At 12:15 p.m. General French received a message that a large number of Union infantry and cavalry were headed his way. At 12:30 p.m. French ordered Sears to withdraw and Young and Cockrell were to follow an hour later. The fighting continued as word was slow to get to the proper people.(57)

About 1:00 p.m. (another source states the time of his wound at 10:00 a.m.) General Corse was wounded by a rifle ball that incapacitated him for 30 or 40 minutes. Colonel Rowett then assumed command. He gave the order to cease fire in order to conserve ammunition for the next attack. When General Corse heard this he thought that Rowett was going to surrender and shouted "No surrender, by God Hold the fort." Just then Colonel Rowett receive a head wound that put him out of action. By this time General Corse was back in command.(57) The men tried to fire and stay under cover at the same time. The enemy had concentrated a murderous fire and it was difficult to get a shot off. The 7th Illinois with their 16 shooters pumped out shot after shot as fast as the could fire.(43)

Part of the 7th was taken prisoner around this time. Here is an address given by Lieutenant James Crawley, Co. I during one of the reunions of the 7th Illinois. He said "I was taken prisoner at Allatoona Pass October 5, 1864, about 1:00 in the afternoon. The regiment was ordered to retire to the fort. There were 39 of us out of the regiment that were left firing our Henry rifles and did not hear the order to retire. We were left out in the rifle pits and when I emptied my gun and looked around, the hill between us and the fort was swarming with rebels. We turned our fire toward the fort but where one rebel would fall there would come a dozen in his place. I emptied my sixteen shooter twice and was down on my knees loading again when I looked up and there stood a Johnny Reb within about twenty feet of me with a musket leveled at me. He wanted to know if I surrendered and I told him I guessed I couldn't do any better. They marched us over where their artillery was and then we found that our forces had not surrendered, and the enemy was retreating. Under the circumstances we could do nothing less than retreat with the enemy, and we marched all the afternoon till about sundown, when we went into camp at New Hope Church, about ten miles from Allatoona Pass. If the boys had listened to me that night we could have made our escape just as well as not. About dark it began to rain very hard, and there were 102 of us and only 30 guards, ten on relief, and the remaining 20 were in among us. I could have picked up two or three guns at any moment. I proposed to my comrades that two of them go and engage each guard in conversation and at a signal each two men grab his guard, throw him inside of the guard line, grab the guns and march the rebs back to Allatoona Pass. We could have been back before daylight and not fired a shot. I have always been sorry that I allowed the boys to persuade me out of making that attempt." Lieutenant Crawley and the others ended up in Millen Prison.(40)

The artillery was silent for want of ammunition. One brave fellow, whose name has since been forgotten, volunteered to cross the cut, which was under enemy fire, and go to the fort on the east hill and procure ammunition. Having executed his mission successfully, he returned in a short time with an arm-load of canister and caseshot.(43)

About 2:30 p.m. the enemy were observed massing a force behind a small house and the ridge on which the house was located, about 150 yards to the northwest. The dead and wounded were moved aside to make room to place a piece of artillery to command the house and the ridge. A few shots from the gun threw the enemy's column into great confusion. The Union troops them poured in a devastating and continuous fire from their Henrys and muskets that made it impossible for the enemy to rally. From this time until near 4:00 p.m. the advantage belong to the Union troops. Shortly thereafter the last of the Confederate army left the field, leaving their dead and wounded.(43)

After failing to capture the garrison and supplies an effort was made to destroy the supplies. A Confederate Colonel, with a lighted torch, was within a few feet of the store house when killed by a shot from a guard. This was a perfectly place shot in the middle of his forehead. If not for this shot the large accumulation of supplies stored there would have been destroyed. Had the Confederates been successful in burning the supplies it would have endangered the Atlanta campaign and the march to the sea.(44) It could be that this bullet came from a Henry repeating rifle.

Several times during the battle General Sherman tried to keep in touch with General Corse at Allatoona Pass. Sherman was at Kenesaw mountain some 20 miles away. He relied on the signal corp. Two of the men on the receiving end at Allatoona Pass were W.E. Lawless of the 7th Illinois and F.A. West. One of the famous messages sent by General Sherman and received by these men was "Hold the Fort for I am coming." (44) While the battle of Allatoona was at its height General Sherman was straining every nerve to throw a strong force in between Allatoona and Dallas, so as to cut off the column making the attack. The Confederate records show that it was an apprehension of this movement that caused General French to withdraw from before Allatoona but the fact remains that after 14 hours, skirmish and battle he was repulsed at every point with heavy loses.(43) Loses for French were listed as 287 dead and 783 captured(42) including General William H. Young. In research of the records of the battle, Captain John A. Smith of Company E, 7th Illinois gives a figure of 1800 killed and wounded. This figure comes from the fact that on September 21, 1864 after the battle of Lovejoy Station French's army had 4,700 men. The report of November 14, 1864 shows 2,900 men with the only battle being Allatoona Pass.(51)